One day at the end of April, my husband Annibale (Hannibal in English) and I decided to try out cycle touring. Good for our bodies, and everyone else. There would only be some sweat oozing out of us, but no other noxious emissions.

The problem was, of course, where to go on our bikes: forests or towns with art galore? Climb slopes or stay on the flats? Ah, an embarrassment of riches where I am plunked down, in a flat town in Veneto between the mountains and the sea.

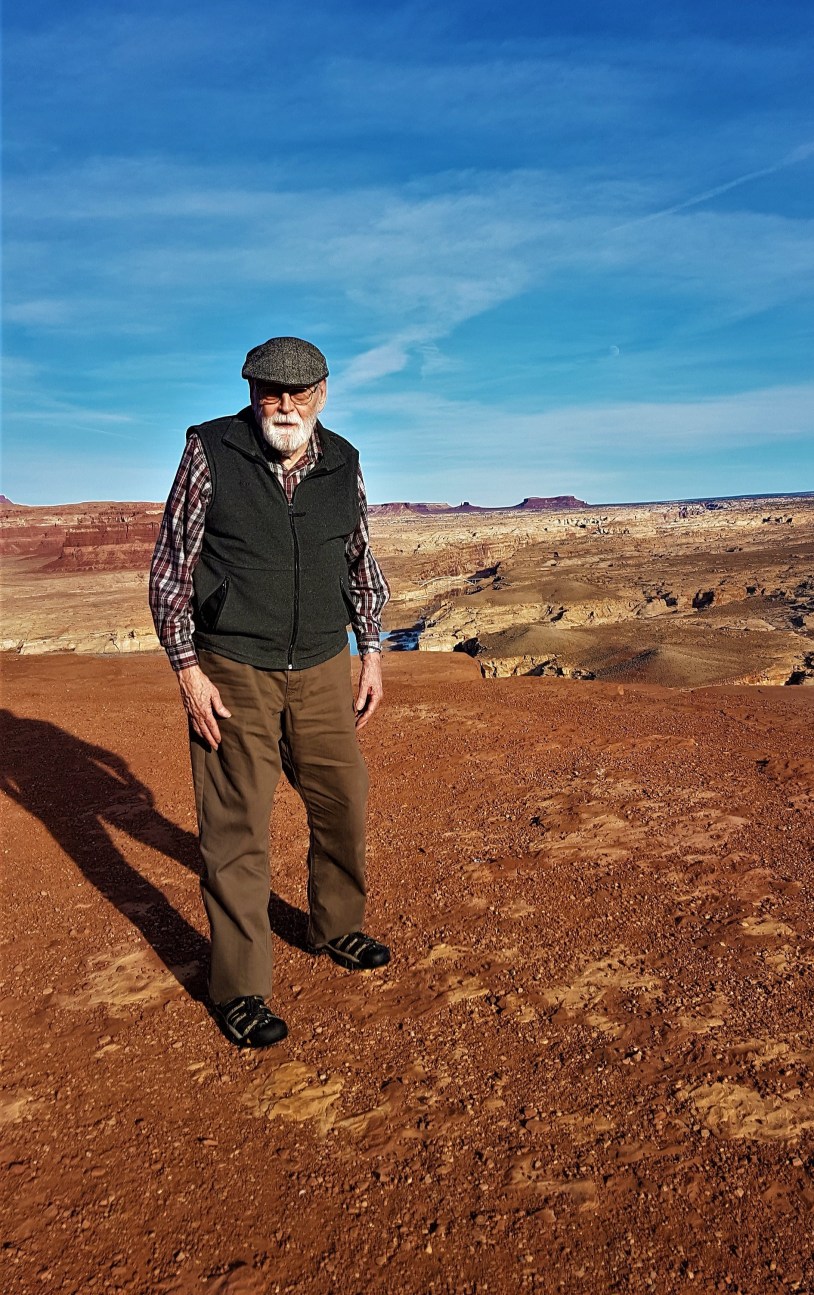

Why not simply put it all in the hands of an app? What could go wrong? So that’s what my significant other did last spring while I was away to comfort my old dad and say hello to our newborn granddaughter. The morning after I returned, via London, where I got drunk on beer at Heathrow for lack of anything better to do during my 7-hour layover, the alarm went off and I was dragged out of bed. ‘We have to get to Austria before dark!’

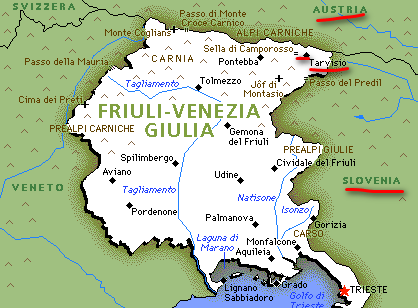

I dozed on the road to Friuli-Venezia Giulia, the region east of Veneto. Venezia Giulia is the southeastern coastal spur which includes the city of Trieste, and Friuli is the rest. By the way, if you haven’t heard a thing about the latter, don’t worry. It is one of the least known parts of Italy. The same goes for Molise, the ‘region that doesn’t exist’ that my husband happens to come from (next post).

We drove in our diesel-fueled automobile to a spot which would get us closer to our destination. It wasn’t right, it was going against the whole ethos of doing things off the grid (apart from all that airplane travel…), but Komoot, our trusty digital guide, had come up with an ambitious ride for the amount of time at our disposal. We couldn’t let it down, according to the human next to me who’d actually empowered the app.

But I was game. As game as a wreck suffering from jet lag who hadn’t been on any sort of bike in months could be.

We parked in front of the Pontebba train station and headed north on a path that even my father could have handled with his walker.

Now, we were in a territory nestled between Austria and Slovenia, with some communities that still speak German and Slovenian. For this and other reasons, Friuli has a special autonomous status. That means that its local idiom, Friulano, more similar to Italian, has special status as well, and is called a language, as opposed to a lowly dialect.

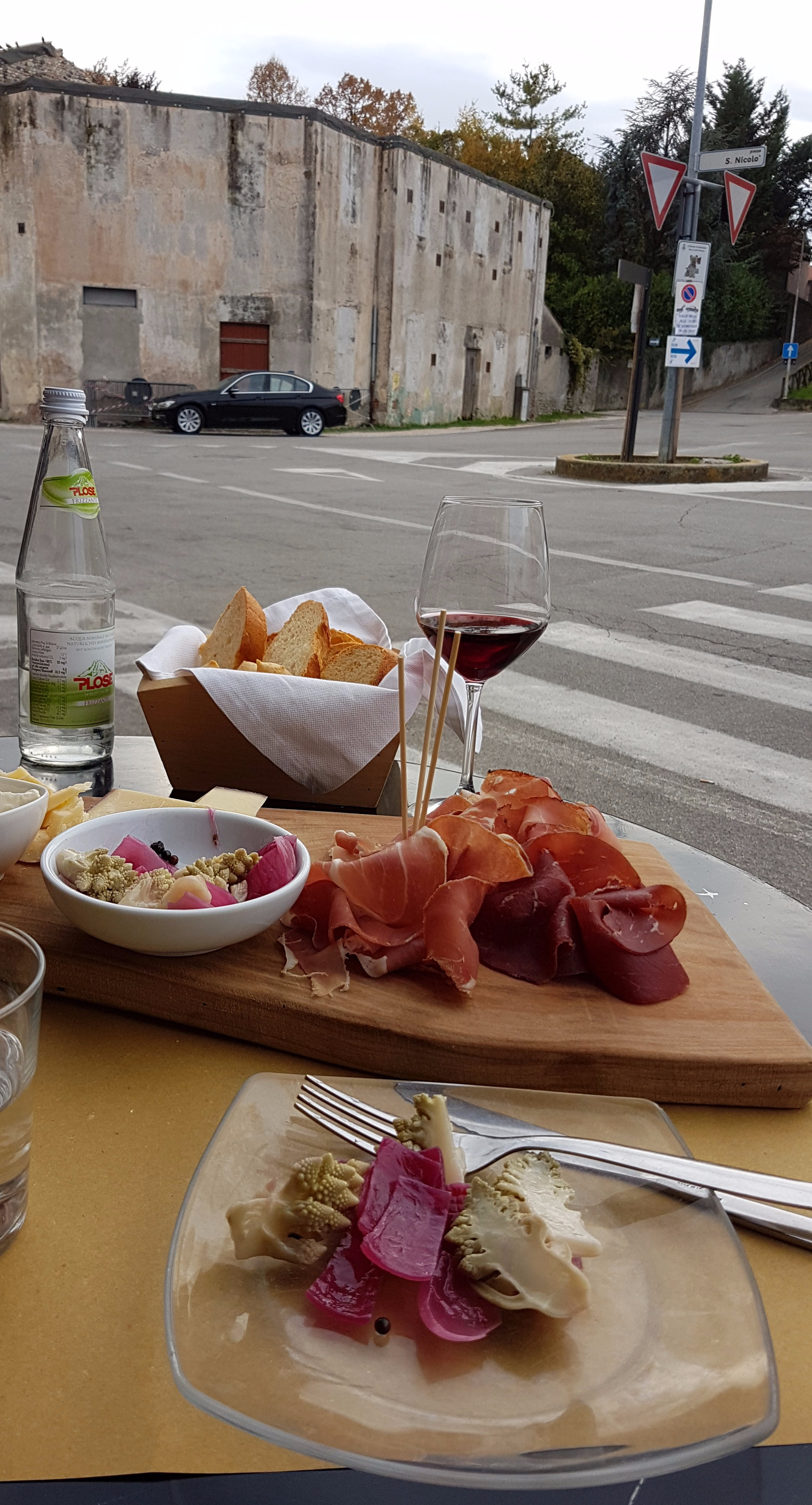

Friuli produces wine, has mountains, and water flowing from the mountains, and a

vast plain, and beautiful towns which are not very large. Sparsely populated, one could say. A frontier land that is also prone to earthquakes, alas. It also saw quite a bit of fighting in WWI between the Kingdom of Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and its German ally.

Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms describes the chaotic Italian retreat of 1917 from Caporetto in present-day Slovenia. My husband’s grandfathers, young men who had

hardly ever left their little hamlets in the Appennines of southern Italy, were both

swooped up and conscripted to fight in the Alps of northeastern Italy during the Great

War. Despite having been wounded in Friuli, one grandpa always talked about going back

to visit that place in the wild blue yonder where he came of age, and didn’t die.

The ascent to Austria on the bike trail was so gentle that even my flabby legs didn’t feel it. And what a fine surface, set apart from the main road, with views of the river Fella below and the peaks of Carnia (northeastern Italy) and Carinthia (Karnten in southern Austria) and Carniola (Primorska and Gorenjska in northwestern Slovenia) standing in all their April splendor. You couldn’t ask for more, really.

We reached Tarvisio in no time. It lies in a land of three countries, a Dreilandereck, one of those handy German words that describe a whole situation in five or ten seconds. You can consult Mark Twain’s highly-esteemed essay The Awful German Language (https://faculty.georgetown.edu/jod/texts/twain.german.html) for more on that.

Tarvisio is famous for being in that little corner. And for having been wrested from Austro-Hungarian control during the devastating territorial war mentioned previously. Notice that the gracious sign below is written in four ways: Italian, Friuliano, German (the latter two identical here) and Slovenian.

So far, so good. We ended up in a woody area near the extinct border between Italy and Austria, where we were following a scruffy-looking man in his late 60s with hefty panniers on both sides of his bike. He looked as if he hadn’t had the chance to take a shower lately. At a certain point a car shot out of a side road that had access to our path, forcing our cohort to make a sudden stop. ‘Asshole’, I heard the poor guy bellow. I sped up to talk to him, thinking he might be from my homeland. But no, he was a German from Bremen. Wow, I thought. Has ‘asshole’ entered the German tongue, the same way Americans say kindergarten and scheister lawyer? Would have to ask my Teutonic colleagues about that. Full disclosure: I’ve been trying to improve my basic knowledge of the formidable German language on Duolingo as I think it’s good for my brain. No matter what Twain says. Anyway, the Bremener had cycled all the way from the North Sea to Venice and was now pedaling back. He deserved to tell the brutish automobilist off.

We were all heading for Villach, a small city in Karnten with a Slovenian name. Makes sense. The country we associate with The Blue Danube and Sissi and Sacher Torte was once part of a sprawling political entity with a whole slew of peoples and tongues. Many ethnic groups were eventually able to create their own nation-states, which didn’t necessarily include all the areas historically inhabited by them. Languages leave traces.

We crossed into Austria, where the bike path became less idyllic. We were inhaling car exhaust as we pedaled next to traffic-ridden thoroughfares in Villach, until we turned off the main route to go to an outlying village we’d chosen for a cheaper overnight stay. There we found the sort of Sound-of-Music type countryside we’d been expecting. Tidy green fields, and an understated church. And once we arrived at our modest hotel, I discovered that studying German can actually be useful, rather than simply entertaining or a way of staving off dementia. Just because English is the modern-day lingua franca doesn’t mean, of course, that everyone speaks it. Not everyone is into that kind of thing, in fact.

So I managed to understand the most crucial things, such as where the only restaurant in the entire area lay. Just a twenty-minute walk. What a relief, as our loaded gravel bikes needed a rest for the day.

I was also lucky enough to have studied, on my app, all about the love of German-speaking people for white asparagus. A goodly vegetable, full of nutrients. But what makes it so extraordinary? I reminisced about a corn-on-the-cob festival in Wisconsin I went to as child. There was a feature where you could pay five bucks for as many cobs as you could knaw on in 15 minutes. I’m sure swallowing small slices of pale slender stalks cooked in different ways is much more elegant. And therefore makes people go wild with delight, somehow.

In any case, all the lessons about the famous Spargel turned out to have a purpose. They gave me a heads-up on why the local gasthof had an entire menu dedicated to this wondrous vegetable. Deep-fried asparagus wrapped in bacon may not be particularly healthy, but it did go down the hatch quite easily (along with some more beer).

Back in our room under my eiderdown, still suffering from jet-lag, I pulled out the reading material that I’d stuffed into my case. A slim paperback in lieu of an extra pair of socks. Wunschloses Ungluck, by the Nobel Prize winner Peter Handke. Difficult to swim through, but not because of its style or unbearable title (translated as A Sorrow beyond Dreams, although I would label it Dreamless Misery. But my German is execrable, so what do I know?). I was simply biting off more than I could chew. It’s a bad habit of mine which I still haven’t rid myself of. Now, I knew the ending was bad – the author’s mother was going to kill herself – but it was something a friend had once given me, it had been sitting on a shelf, neglected for twenty-some years, and it took place in Karnten. I opened it to the first page.

It turned out that Handke’s maternal grandfather was of Slovenian descent and was the first of his line to actually own property and thus be rich enough to marry. His forebears were farm laborers who procreated without the luxury of becoming husbands. I thought of my own great-great-grandfather in Sweden, who did marry, it’s true, but was also landless and so poor he had to live ‘on the parish’ – 19th century Scandinavian welfare. Some of his nine children, including my great-grandmother Nina, emigrated to America to escape that fate. I then nodded off before I could get much further than understanding that women living in rural Carinthia in the early 20th century weren’t supposed to expect much out of life. Their lot was to have a few laughs before the grim reality of marriage, children, cooking, and death.

We cycled eastward the next day. An easy ride along the Worthersee, a long lake surrounded by hills. Ah, I was in better condition than I thought. This was a bed of roses.

We passed through Klagenfurt, the busy capital of the region, had coffee, and turned north, just to put in a few more kilometres. All quite leisurely. And it turns out this is known as the sunniest part of Austria! Handke might disagree with that appellation, however. One of his sentences I actually understood without a dictionary focused on endless days of rain and fog.

Only a little bit of grayness for us, though. We made our way up to Sankt Veit an der Glan and stayed in a fantastically decorated hotel. Austria is also known for art and design. Think of Schiele, Klimt and Hundertwasser.

That night at dinner, over beer, my husband mumbled something about the road ahead. He was a little worried about the third day’s route, which would take us south over the Karawanks mountain chain into Slovenia. ‘It might be a bit steep,’ he said sheepishly, as he ate some more Spargel. Grilled this time, with sausage on the side. ‘Steep’? I was having trouble understanding him with all the noise from the other ecstatic spargel diners around us. ‘Yes, and it might rain too…it turns out…’. ‘Do we have any alternative?’ I shouted above the din.

I continued with Wunschloses Ungluck in our trendy little room. I would go through entire paragraphs where I might make out two words. So much for English and German both being germanic languages. The Normans did English such a big favor by coming over the channel and forcing their more worldly French on the provincial Anglo-Saxons. Just think what we’d be left with if they hadn’t.

Handke’s mother had gotten away from her family farm and started working in a hotel, just before the Anschluss (the German annexation of Austria in 1938). Then the war started and she got pregnant, by a German she loved, but who was already married. Then she in turn married a man she didn’t love, just to give her son a father. The misery was starting, although she didn’t realize it right away. They went to Berlin.

‘This will be a real test for us,’ Hannibal warned me as we packed the next day. Not difficult as I hadn’t brought much. I did make sure our cheap ponchos, all of 2.5 euros a piece, were on top. But why did hubbie have such a furrowed brow?

We could see, once we reached the river, that that the landscape was changing. So much the better. We needed a challenge. We stopped to have a little sandwich in Ferlach, at which point we were already halfway to Lake Bled in Slovenia. All was well.

We then started on the forest road, and felt the first sprinkles of rain. The weather was starting. Time for to whip out our featherweight protective gear.

We came around a bend and an Austrian woman called out to my husband in German, telling him he looked like an angel! The transparent plastic we were swathed in, lifted by the breeze into wings, did give us an odd aura. The last time someone likened Hannibal to a heavenly creature was when we lived in Rome. Not a city where pedestrians are king. My husband stopped his car to let a tour guide lead her group of aging sightseers over a crosswalk near the Colosseum. The guide came up to his window to confer angelic status on him right then and there. She’d been standing on the curb for twenty minutes waiting for another driver to obey the law, or simply show some kindness. Hannibal was engaging in the latter behavior, she understood.

I was brought back to the present by a sudden realization that I was suffering. We were now on the main ascent to the Loibl-Ljubelj Pass between Austria and Slovenia. My gravel bike seemed to weigh twice as much as before. And my brand new bikepack, which slid onto a plastic rack behind my seat, felt as it were made of cement.

I couldn’t get up all of the tough bits (some at 15%). My husband’s bike having less sophisticated gears than mine meant that he had to jump off his even more often and simply push it up the bad parts. I found that getting off was just as bad as sitting on my increasingly painful seat. I also didn’t have the arm muscles to push or drag a loaded set of wheels up a hill. And the air-filled ponchos were useless. We were bedraggled angels halfway up.

Then we passed by a sign indicating a KZ Gedankstatte Mauthausen. I stopped to think about what that meant. Mauthausen was an infamous Nazi concentration camp in another part of Austria. But there had been a branch here too, apparently. The memorial didn’t seem to be open, though, and I didn’t have a good internet connection on my phone. So we continued going up the main road, at our very slow pace, until we reached a tunnel. A long one, it turned out, over 1.5 kilometres long, and narrow. We cycled on the equally narrow raised sidewalk which consisted of vertical slabs of cement placed next to each other. I kept imagining my tire getting stuck in the slit between the slabs and me being hurtled into the lane full of traffic to my left. I wouldn’t recommend that particular route to anyone. It’s probably illegal for cyclists, as a matter of fact. Not that that had stopped us, not on Komoot.

Once I did have a good connection, later in the day, I found out that the tunnel itself was infamous. It was actually built by prisoners from the local branch of the Mauthausen camp during WWII, some of whom died while constructing it or were executed in northern Austria when they could no longer work. A few survived and walked through the tunnel to Yugoslavia at the end of the war (Slovenia became an independent country in 1992, after having been part of the southern Slav nation-federation of Yugoslavia since 1918).

Every country has its history. Some worse than others. And some events are in the more distant past but others still too recent, and shocking, and shocking also because they are recent, to ignore. Haven’t human beings evolved at all? I think of the plaques I now see in the US reminding people of massacres and lynchings that took place in pretty spots in Virginia, for example, before and long after the end of slavery. And Austria is, in fact, the birthplace of Schnitzler, Freud, and Hitler.

Here is some more information about this particular site: https://www.mauthausen-memorial.org/en/Loibl/The-Concentration-Camp-Loibl

We made it out of the harrowing tunnel, and found ourselves in Slovenia. On a saddle in the Karawanks/Karavanke (a mountain chain in the Southern Limestone Alps, which include the Dolomites). There was still a bit of snow higher up. I turned to my husband and told him that although we were utterly exhausted, we weren’t actually soaked. Only light precipitation in Karnten, after all. No sooner had the words popped out of my mouth than the heavens opened up and drenched us with an icy downpour. I took off down the busy highway without further ado. I paid no attention to the cars and trucks I was racing alongside or the floating sheets of water on the road.

I got to the bottom of the hill first. But where was my companion, usually so much faster than me? He caught up five minutes later, aghast at the risks I’d taken. ‘You could have been killed!’

I explained that I had lost my powers of reasoning. I just wanted to get to our hotel room in Lake Bled, the inauspitious-sounding Bled. A famous spa town in northern Slovenia on the shores of a lake with an steeple-topped island in the middle, surrounded by hills, that doesn’t have anything to do with bleeding. Still…

‘We somehow missed the track that Komoot suggested! It’s back up there!’ I glanced up at the top of the slope. Unthinkable. And I hadn’t seen any sign of an opening on my way down. My husband showed me, once we’d found a bus stop with a roof, and he was able to wipe the screen of his phone dry, that he was referrring to a steep rocky path with boulders that would have taken us up to another saddle, from which we have been catapulted down into the next valley. A fearsome short-cut that we might have trouble even finding in a storm. ‘We’d have to drag our bikes up that,’ Hannibal explained. ‘And drag them down, too,’ I whispered.

I explained that my crotch was on fire and that I was probably suffering from hypothermia.

So we checked our map again and decided to cut westward across the countryside to Bled to avoid the main thoroughfares. The route also looked slightly shorter.

It wasn’t raining quite so much, and the road we’d chosen was lovely. Meadows and fields and little stands of trees in their seasonal shade of light green. I would’ve taken many pictures at any other time. An ascent to each little town, and a descent before the ascent to the next one. Up hill and down hill, over and over and over. All those clusters of houses that had to protect themselves from marauders in the Middle Ages were serviced by our byway. So unbelievably charming. My leg muscles were inflamed and my head was spinning.

We finally reached the outskirts of Bled, at which point there was even a bit of bleeding going on. Never mind. We found our hotel and I fell off my bike. I hung on to the bannister to get up the staircase to our cold room. There I discovered that my new bike case and bags weren’t waterproof! I squeezed the water out of my shoes, warmed my hands over the tepid radiator and hobbled across the street to a gostilna where we each had a plateful of wienerschnitzel. My husband told me I was heroic. I said that I was just plain clueless. It was actually the most grueling workout I remembered ever doing in my whole life. The combination of no conditioning, bad clothing, and not knowing the route was downright foolish. I had bitten off too much, once again.

And to continue in that trend, I turned back to my book. What happened next to Handke’s mother?

She and her German husband got out of East Berlin in 1948. She used her Slovenian to talk to a Russian guard at the border crossing. The family ended up back on the farm in Karnten, where she had more children, and also performed abortions on herself. Her husband would get drunk during the winter when there was nothing to do, and beat her up. She was curious, she started reading books. I fell asleep.

We took one picture of the truly lovely lake most people come to for a relaxing sauna. But no time for dawdling. We had to get back to Italy.

Our app then sent us on an adventurous route to get up to the northern valley of Kranjska Gora.

Komoot, as far as I understand, was created by a bunch of young men who weren’t too worried about things like safety, private property and so on. They just want their users to get to places as fast as possible. And Annibale delights in doing illegal things he knows he can get away with. He swears that this is his Italianness.

At a certain point, we were told to ride under a bridge on an informal sort of road, and then rumble along in the deep trough of a railway under construction. And then through a tunnel undergoing repairs under a railway that was actually functioning. Tiring, but also so much fun! Breaking rules has that effect on people, apparently.

Our off-track biking did get us to where we wanted to go while bypassing some busy roads. We ended up east of Kranjska Gora, a ski resort in northern Slovenia located on a side spur of the same Adriatic-Alps bike trail we’d taken from Pontebba. We knew that our troubles were over.

The path to Italy was wonderfully paved, just like the entire Adriatic-Alps route. Smooth sailing, which was just as well, because I could no longer sit on my saddle. I stood on my pedals and let gravity take me back to the car.

We did stop to look at the karst Fusine area, just inside the Italian border. Karst, by the way, refers to a landscape full of underground rivers and sinkholes and caves and such caused by its limestone base. It comes from the German name given to the rocky plateau overlooking Trieste, which is also called Carso in Italian, and Kras in Slovenian.

I got home and continued to read my book as I recovered from our trip. I reached the bitter end, not sure I’d actually understood what the son thought about his mother’s decision to end her life. Was he proud of her, did I get that part right? I’d have to start over, I decided. I would be going back to Austria, and I would continue working on the challenging German language.

I also needed to be more constant about my cycling, to make my excursions less dramatic. The Loibl/Ljubelj Pass isn’t even all that difficult, compared to many others that I have done myself. https://climbfinder.com/en/climbs/loiblpass-ljubelj-ferlach

And I had to look for a book by a Slovenian author for my next trip to a small country full of mountains, rivers, caves, and bicycles. But not in Slovenian. Not yet.