“So he wants sheep,” said the man to himself. He shook his head…” (Independent People, p 210)

Some people are always looking for adventure. Volcanoes that might explode at any time, for example. Now, my husband and I actually had no hankering for that kind of thing on our way to Iceland in the summer of 2019. A., instead, was thinking about wildfowl, and I livestock. Because I was busy rereading ‘Independent People’, by Halldor Laxness. Never heard of it? Well, you’re missing out on a brutal and beguiling 20th century saga, worthy of the medieval ones that came out of the island lying atop two continental plates, the North American and the Eurasian, just below the Arctic Circle. All kinds of thermal activity there. Geyser is, in fact, an Icelandic word. Saga too: long stories about people in a wondrous place almost unfit for human habitation.

I first picked up ‘People’ years ago only because of the stubborn-looking creatures on the cover. Then I rushed through page after page. I read about a man fiendishly obsessed with the animals that were going to make him free, on a bit of remote turf spurned by everyone else. Just like his Viking ancestors did, away from their kings and bishops.

Bjartur of Summerhouses only had one life to live and no time to worry about the welfare of wives or children. Subsiding on meal after meal of porridge, or trash fish, all drowned in endless cups of coffee. Coffee! Hardly a drop of liquor. I finished the grim tale, and said, ‘Never again!’

But then I began leafing through the dusty volume once more just before my journey. The second time round there was sly humor, and poetry. And even love, tucked away here and there among the rocks, so to speak.

Phalaropes, and green shanks wandered across the pages too.

I threw the paperback into my suitcase, along with a few summery things, on the 22nd of June, 2019.

An impatient teenager showed up at the Reykavik airport at 1 am to take us to his off-site car rental agency. Our eyes were half-closed. But he threw our bags into his jeep and dashed off on a gravel road to a hill of granite overlooking the great ocean. The sun was just taking a cat nap below the horizon and its light was still hovering around. The solstice wasn’t over yet, by golly. We left our young dealer to celebrate this joyful event with his friends and the unopened cans of beer lining the floor of his little prefab office. Ah, that was a bit more like it.

Then, undeterred by the piece of paper on the dashboard of our basic car warning us about STRONG WINDS and reminding us to NEVER TAKE THIS TYPE OF VEHICLE ON ANY F-ROADS!, we made our way to the capital.

F-roads, f-roads, I mused, as I dozed in the passenger seat. What a rough land this must be.

The next morning, like someone with the shakes, I rushed to the nearest bookstore to stock up for the trip. I managed to find something on local history and another couple of novels by Laxness, not only a great but also prolific writer. One of his stories was about an Icelander becoming a Mormon and moving briefly to Utah in the 1860s. Oh-my. The Latter-Day Saints were already evangelizing in such far-flung parts of the world in their early, unvarnished, polygamous days? Now it’s true that the scenery in both places can be, let’s say, unexpected. The immigrant wouldn’t have felt like such a fish out of water. And maybe that’s where certain non-drinking habits were picked up, by some people.

Drowsy after driving for an hour in a northerly direction, we stopped in the town of Bogarnes to get some stimulants. We found some in The Settlement Center, a museum that was well worth whatever fee we paid. You really shouldn’t be too thrifty when sightseeing, not even in pricey climes. You can always save on food. Not every part of the world has a cuisine to write home about, in fact.

We found out that the island looked rather different when the Norsemen showed up, in the late ninth century of our times. The new human arrivals found trees, by gosh. Some tall ones and many svelte birches, and grasslands, and winged creatures, and a few Irish monks, who then disappeared. The birds still flock to Iceland from far and wide, but the forests, alas, went the way of the monks. And the cows, the horses, and, last but not least, the sheep, were all brought over by the Norwegians along with the Celts they enslaved or married in Ireland and those other British Isles.

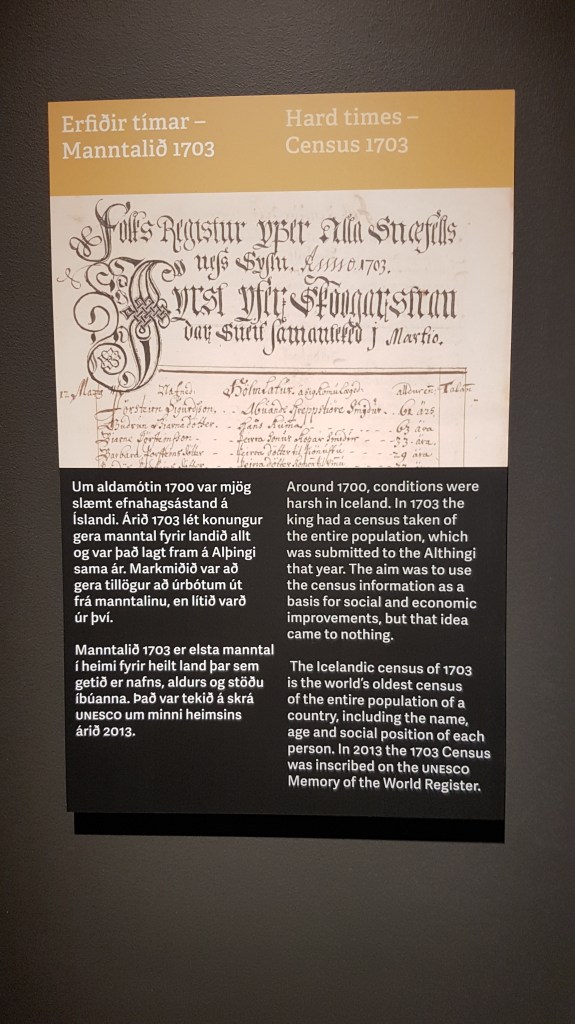

The newcomers were called, appropriately enough, the ‘landtakers’. There was no heirarchy, no monarch, no government. Then the settlers founded their parliament, the Althingi, which sounds suspiciously like ‘all things’, and created an island community now referred to as Free State Iceland. This golden age of taking land and free statedom lasted from about 874 to 1264 CE.

The immigrants recorded the names of the first farms in a register called the Landnamabok. They recorded the names of their representatives at the Althingi. Icelanders are keen on documentation. A young man working at the museum told us that he knew for a fact that he was descended from one of the first pioneers. He had it all in his family tree. Ah, family trees.

Laxness’ narrative was becoming less arcane. Its sometimes inscrutable, and many times calloushero, Bjartar, lived in the early part of the 20th century. An Icelandic everyman who was steeped in the history of his land, he was up against the elements, large landowners, and merchants. He couldn’t be encumbered by ‘feelings’. But he wrote verses. And though he didn’t send his children to school and barely fed them, he made them memorize the ancient tales of feuds and valor and romance.

We continued on our route, which included a ferry ride from the town of Stykkisholmur to Brjanslaekur in order to skip a bay and a peninsula. You just can’t see every one, although I would never say, ‘seen one, seen them all’! No, no. Every fjord has its distinct personality and deserves to be gawked at and photographed, . But we were in a rush to get to the westernmost point of the fjords in the westernmost part of the country, the Vestfirdir. The least visited by people, the most visited by the avian population. And the most reminiscent of the kind of place where Bjartar staked his claim on an abandoned and possibly bewitched patch of soil.

There is one main highway in Iceland, called route 1. It has two lanes, scarcely any shoulders and goes in a slow circle. The roads leading off of the ring road 1 are slower yet, and some are also denominated F. As noted earlier. I could only imagine what it was like in Laxness’ youth, when Iceland was neither a tourist mecca nor independent.

We disembarked and drove like mad to the western edge of the western fjords, the cliffs of Latrabjarg. Maybe not what everyone would endeavor to see, but honestly how can you not feel elated when you are on top of one of the highest birdwatching spots in Europe? Really?

So much to fit in before the endless day ended. The air was downright chilly and the wind was strong. My imagination had failed me in terms of garments. I was shivering and the hood of my thin jacket kept blowing off my head as we wandered along the edge of a grassy field that suddenly turned into an eroding ledge. I could see waves breaking below, where the Denmark Strait meets the Atlantic Ocean. Greenland was the next stop over to the New World. Oh, Greenland!

Puffins, guillemots, gannets and eagles were darting and soaring and feeding their young in a free state. At liberty to come and go.

We then hurried to the one hotel, very practically named the Labratarg, with a room available in the entire area. When we arrived at the lodge, only open in the summer months, the elderly owner told us that there was some food left for us. Good thing, he added, solemnly. It was 9 pm and the next eatery was hours away.

Our international dinner was served to us by staff from Latin America. The owner explained that Iceland has such a small population that it has to look elsewhere for employees during the tourist season, especially in less accessible areas. We drank a little beer, without overdoing it, and then went out for a walk along the main road. It was gravel and it was deserted, apart from some very some weird sounds. A ghostly thing was ricocheting from one side of the road to the other in the twilight. There was also talk of the supernatural in old Icelandic tales. Necromancers and elves and such. We finally managed to catch a flitting spectre in our binoculars. Just a brave little snipe! The lesser snipe, to be exact, beating its wings back and forth so fast we’d have never been able to bring it down with, say, a gun.

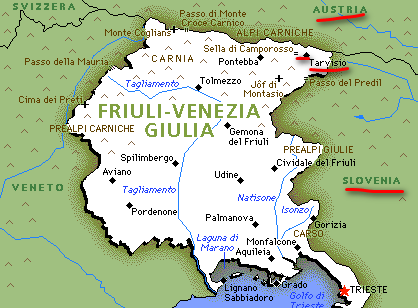

The Vesfirdir on a map resemble a sort of eight-fingered left hand with a small wrist and a huge thumb. A recipe for a meandering trek in a vehicle. Our next drive took us up and over one of the digits, from the Patreksfordur to the Sudurfirdir. The wind did buffet our vehicle, and as I gingerly cracked open the passenger door at the top of one climb, it almost got torn off its hinges. That warning was correct.

Long views of water, and barren mountains. The trees were cut down for fuel and to build small boats. The sheep could roam about and find food. Their wool was wonderful. But the sheep also ate all the edible highland plants, which didn’t grow back easily. There were volcanic eruptions as well. Only 1% of the forests still exist and nearly half of the grasslands are gone. No wonder not everyone was enthusiastic about the grazers.

We stopped to read a sign about a famous saga. Not a dwelling in sight in these denuded uplands, but some deeds were done here back in the heroic Middle Ages that Bjartur studied with fervor.

More driving on gravel roads, with wind and rain. Not many trails to detect. Markers but no actual paths. Some sturdy hikers with ponchos and long staffs were going up steep inclines willy-nilly, in the stark landscape.

Starkness, starkness. There was grass in the lush valleys at the head of the fjords, but not much greenery on any slopes closer to the sea. In fact, quite a bit of scree, with just patches of blue to give them some color. What extraordinary flowers, I thought, those purplish-blue things. Then I read that these Nootka lupine were introduced from Alaska after WWII. A pushy plant which creates controversy. It holds the land, and adds fertility. But it is not native and no one can stop its proliferation. An invader or a godsend?

After Norway took over the country in the 13th century, Denmark then dominated Iceland from 1383 until 1944. By then the more powerful country was occupied by the Nazis. Iceland had invited the US to set up a base on their soil and the new nation was born with the blessing of the country then considered the leader and defender of the free world. How quickly things can change.

So independence came once again for the Icelanders. Independence, after those early, heady days, so reminiscent of the ancient Greek polis, what philosophers enthused about. Some historians say that democracy took shape where it did in the Mediterranean because of the mild climate. People could walk about, and socialize and exchange ideas at all times of the year. But maybe an inclement climate with little to offer the greedy could have the same result.

We started wandering around humpy green hillocks. There were sheep too, contented sheep. Like the ones belonging to Bjartur after life became slightly easier. When his family was no longer starving, during WWI. As the character says, slaughter on the continent, good business for the Icelanders. Bjartur the everyman was never worried about being genteel.

After a few nights in Sandfell, in an expensive hotel with school cafeteria-style food and tiny bathrooms and hard beds, we started on the long gracious slog from Isajordur over to Holmavik. A billboard for a campground advertising a natural hot pot caught our attention.

We paid a small sum of money to use the changing rooms to put on our swimming suits under our clothes and then walked across a field and over a stream to a windwhipped hillside with a hot spring filling a pool not much bigger than a bathtub in a luxury hotel. I tested the water with one toe and then dropped in, to defend myself from the fresh air of summer in Iceland.

We then decided to have, yes, that black live-giving beverage, coffee, in the campground cafe. It was a large room where they also sold maps, souvenirs, and, finally, at last, thick homemade sweaters. Where had they been hiding the last few days? The unique seamless pieces were hanging on a rack near the cash register. I tried on all five and decided that only one would fit me or my daughters. 180 euros, under the table. ‘You see,’ the cashier explained, ‘they are just handknitted by local women in their spare time…nice ladies…’ There was, fortunately, a handy ATM in the facillity, where we could get the dough to purchase this truly national treasure.

Feeling more at home, clad in the waterproof fabric of the commonwealth, I was now ready to explore other places. We spotted more greenshanks and redshanks and terns in the torquoise or agate colored water we passed as our teeth worked on some dried fish jerky I’d bought at a convenience store. The stringy, salty fish with its leathery skin still intact might have been something even Bjartor would have disdained. Or not. Land of tough people.

We were now leaving the western hand of the country. We had to go to other parts and check out some thundering waterfalls, and see other bird species. Suddenly, our dirt road became paved as we were coming down a steepish hill. The car jolted, unused to smoothness. We had come out of the wilds. Alas.

There were big tour buses and many cars on the road east, following the undulating northern coast. We went to a bakery in a little port town and bought another sweater, cash down. This time there were four of them hanging on a rod next to the bread and cakes. The ATM was just across the road.

I saw a government-managed liquor store in the same shopping area. It looked identical to what you find in Utah. This was also astonishing. No advertising, a barely visible sign on a plain building. But yet, plenty of people were coming in and out, carrying large bags. That evening we went to a restaurant in the countryside to eat some lamb. My husband and I ordered beer, and then he ordered another one. The teenaged waitress glared at us. She was part of the Christian Women’s Temperance Union crowd, clearly. Bjartur might have agreed, although he wasn’t sure he was a Christian. Still had that heathen in him, able to survive among the hot pots and lava.

The responsible young woman certainly had a point. Who would want to navigate route 1 when tipsy? Or venture onto a diabolical road by mistake? There were plenty of brands of artisanal brews on the menu, though, and everyone seemed to be enjoying their amber drinks. It was clear that Iceland was as divided about alcohol as it was about the purplish-blue flowers.

Our last night out on the road we stopped in the birthplace of the famous writer Snorri Sturluson, the man who wrote down all the Norse myths about Odin and Freya and so on, saving the fireside tales on parchment for eternity. We would, in fact, not know about Thor’s hammer if it hadn’t been for this energetic man of letters living on an island with geysers in the 13th century.

I went up to the door of the neaby bed and breakfast place I’d booked. A woman came out to greet me enthusiastically in her local tongue. ‘I’m so sorry!’ I said apologetically, ‘I don’t speak your language…’ Our host was floored. ‘But your name looks Icelandic!’ she said in perfect English. ‘No, no, it’s actually Irish…’ ‘Oh, I’m also terribly sorry,‘ the good woman replied. ‘I don’t speak any Irish…’ ‘Me neither…’. I smiled and shrugged to show there were no hard feelings. How could one explain to an Icelander, of all people, that not all idioms or cultures make it out of the great maelstrom of time?

I thought that was that, until she served us breakfast the next morning.

‘I’ve had a think,’ the dark-haired lady said. ‘You know, the Vikings brought Celts with them long ago. So we are related, after all.’ She patted my hand.

She was right, of course. We are all related and connected in some way, not just through Irish thralls dragged to Iceland over a thousand years ago. I thought about this as I wore my new sweater during the dread winter of 2020, in Italy. I discovered during that first pandemic lockdown that I didn’t need to turn up the heat at home with all that thick yarn on me. What a grand thing.

I was also able to save money on fuel during the next winters, with prices going up every month. Invasions and so forth. So my investment paid off and I also helped the rural economy of that not-so-faraway land. Laxness’ land.

I would go back someday, to the fantastical island. European, but not only. To see more cosmopolitan birds, and volcanoes, and trundle along mysterious thoroughfares. To frolic in the crisp summer wind, like a sheep, the grass-devouring, erosion-promoting animal so beloved by the free Icelanders.

Recommended reads:

Independent People by Halldor Laxness

Viking Age Iceland by Jesse Byock